I guess you could call them ‘legendary.’ In any case, they’re more ‘legendary’ than most of the crap that is being sold as ‘legendary’ in these limp times of recycled pap. OK, OK, old fart mode off.

HAM is one helluva band and have been since day one. I first encountered Sigurjón Kjartansson (guitar, vocals, songwriting) in a bus going to Kópavogur from Reykjavík sometime in the spring of 1988. I had already released some music on my tiny indie label Erðanúmúsík, and Sigurjón wanted my help in releasing the first HAM single. “Sure,” I said. I don’t think I had even heard HAM at the time but Sigurjón was very eager and convincing. Nothing would come of that single, but we still hung out and got to know one another. He produced S.H. Draumur’s last record (S.H. Draumur is my band, as it were) and I rehearsed with HAM for a while and played guitar with them at exactly one show.

Now, twenty-three years later, the two of us are sitting at Café Haiti. HAM’s first studio album for twenty-two years has just been released upon the hungry masses. It’s called ‘Svik, harmur og dauði’ (“Betrayal, Grief And Death”). We’ll talk about that album later, but we should start by learning about Sigurjón as a young boy, and how he became interested in music.

Groundbreaking shit for a six-year old

“Music was always around me as a kid. My parents were very involved in music, conducting choirs and teaching it. We lived in Reykholt in Borgarfjörður until 1975, when we moved to Ísafjörður [Sigurjón was born in 1968]. I got my pop upbringing from my older brother Sveinn. He opened my eyes to Slade, which was groundbreaking shit for a six-year old boy. Just stunning stuff. The first record I owned was a Slade album.

When I was eight, I had developed an interest in disco, and I remained a huge disco fan until the age of twelve. For the Christmas of 1980 I hoped to get the new Helga Möller Christmas album as a present, but Sveinn, always the important influence, gave me ‘Geislavirkir’ by [Bubbi Morthen’s seminal punk rock band] Utangarðsmenn instead. I had no interest in the album and told Sveinn I’d exchange it after the holidays, but he insisted I give the album a go. So I went up to my room and listened to the record with my headphones. Thus, what happened on Christmas Eve of 1980 is that I went from being a boy into being a man. I was spellbound by that album, and still am. In fact, I still own the same copy, and I still listen to it a lot.”

A punk-rocker in Ísafjörður

Under Utangarðsmenn’s spell, Sigurjón became a punk-rocker. Being a punk-rocker in small, small Ísafjörður (about 4.000 people lived there in 1980, which is more people than live there now) was a lonely existence.

“Sveinn owned a bass and an amp and played with some cover bands. He was such a good older brother that he didn’t mind me hanging out in his room, so I learned to play the bass by hanging out there and playing along to his records. I soon became quite good, and could correct Sveinn when he was playing the songs wrong. I quickly got fed up jamming along to Status Quo songs, or whatever, and started writing my own.”

“I eventually started dreaming of forming a band. And then I formed a band. My first one was called Andstæða (“Opposite”) and it was quite peculiar. It started out as a duet with me playing the drums and another guy screaming. It was very difficult to find someone to play with in Ísafjörður. I was capable on most instruments, and often I wished I could just clone myself and do everything. I eventually managed to train two guys into being fairly good bass players, but I never found a guitar player, so Andstæða never had a complete line-up. I envied young bands in Reykjavík that I read about in the newspapers.”

There were once four record stores in Ísafjörður

Sigurjón made connections and could keep up with what was going on in the big city.

“Bjarni Brynjólfsson, who is five years my senior, just like my brother Sveinn, was well hip to the world of punk and new wave. He was an only child and didn’t mind hanging out with much younger boys, acting as a kind of wise old man to us imps. He organised bands like [legendary punkers] Þeyr to visit Ísafjörður, and sang in a punk band called Allsherjarfrík (“General Freaks”). He knew [future Sugarcube] Einar Örn and brought Crass records from Grammið in Reykjavík [a historical record store that factors heavily in the making of The Sugarcubes and Bad Taste Records] to sell from a little shop he had in his bedroom. This place was my musical oasis. A bit later I visited Reykjavík and stopped by at Grammið, who started using me to ferry records back to Ísafjörður. When I met Einar Örn in the shop, his first question was always: When are you going back to Ísafjörður? So I brought parcels from Grammið to the Ísafjörður record stores. Can you imagine, at the time there were four record shops in Ísafjörður! Eplið, Póllinn, the bookstore and Sería. And Bjarni’s bedroom on top of that.

When punk happened everything that had come before it was violently deemed obsolete. “It was music’s last revolution, I think, negative and angry. For years, I kept thinking: ‘when is the next revolution coming?’ But it never came. Instead, music just became abridged. Parents and kids listen to the same music today. My sons and me have basically the same musical tastes, which is really silly. When I was listening to Purrkur Pillnikk or Discharged in the old days, my parents would ask me to turn down that racket. And today my sons ask me to turn it up!”

Enter the promised land

Sigurjón says he is a record mogul in hiding. In Ísafjörður he released two cassettes on his ‘Ísafjörður über alles’ imprint; a compilation called ‘Ísfizkar nýbilgju grúbbur (dauðar og lifandi)’ (“New wave groups from Ísafjörður (dead and alive)”) and a cassette by his own Ónýta galleríið (“The Defunkt Gallery”), an experimental “band”, strongly influenced by the mighty Fan Houtens Kókó. In 1985 he finally left the small town and moved with his parents to Reykjavík, or Kópavogur to be exact.

“It took me some time to obtain footing. It was such a promised land for me. Being from the boonies, I had enthusiastically followed what was happening in the city, probably more so than most people living there. I had desired to live there for so long. I enrolled into MK (“The Kópavogur College”) and slowly fell in the circle that would become HAM. In the summer of 1985, I was had a job erecting fences with [HAM bassist] Björn Blöndal, and through him I got to know [HAM singer] Óttarr Proppé. They were from Hafnarfjörður.”Forming a rock group wasn’t Sigurjón’s first choice of creative outlet.

“Me and people like Óttarr and Jón Gnarr, whom I had gotten to know through mutual friends, always had the dream of making movies. I owned an 8mm camera with my uncle Þorgeir Guðmundsson, and we were always trying to make movies. At the time we were very much inspired by (art gang/rock group) Oxsmá, as they had made such great movies [for instance sci-fi short ‘The Oxsmá Planet’ and the rarely seen Icelandic hippie dramedy ‘Suck Me Off Nina’].

“I am not a dictator in the band though. Most of the time, the other members know better than I what is a good HAM song.”

In 1987, I decided to go on a short London trip to visit Bjarni Brynjólfsson, who was studying there. The Sugarcubes were taking their first steps at the time and Bjarni dragged me to see them at The Town & Country Club, where they were supporting Swans, a band I had never heard before. Seeing Swans had tremendous influence on me. The concert has been called the loudest gig to be played in London, ever. I was totally amazed and came back full of inspiration. I told Óttarr that this was it. We should just stop this movie bullshit and become musicians. That happened to be right. We were nineteen years old and spent our days hanging out in coffee shops, always saying and thinking: ‘We should be doing something!’ When HAM had performed a few times, we said to ourselves: ‘Ah, now we’re finally doing something!’ Óttarr and I have always felt like brothers in art. We have always had an inside pressure to be doing something. HAM is really the result of the fact that it is much easier to form a band than to make a movie.”

Blood and horror

The movie speculations did boil down to one short film, ‘The Gay Killer.’”It was shown once at some short film festival at Hótel Borg. I haven’t seen it since, and it is probably forever lost by now. Jón Gnarr played an insane homosexual who lured men to his apartment to kill them. I might have played a pizza delivery boy or his boyfriend, I can’t remember. In the end I was naked; he had tied me up and was busy murdering me with an electric drill. Björn Blöndal was the camera man. This was a big splatter film, with gore and all. We were much into the world of sickness. Mass murderers and serial killers were all the rage. Everything sick was in. It was very important to be sick. It was almost like a contest of ‘who could be the sickest and view the sickest things’. It was the zeitgeist. It’s no coincidence we’ve been called the ironic generation. All this got transmitted into HAM. We decided to make noise, and all the lyrics had to be about blood and horror.”

Making fun of heavy metal

HAM started rehearsing as a band at the end of 1987, and played their first concert at Tunglið (a club that has since burnt down) on March 10, 1988. Icelandic pop icons Sálin hans Jóns míns were playing their first gig ever at a club in the basement. A big day for Icelandic music, indeed. The different periods of HAM can be split between the three drummers that have played with the band.

“We were just four in the beginning; me, Óttarr, Björn and the first drummer Ævar Ísberg. We made our first EP, ‘Hold’ with that line-up. There was a valuable unity in the band at this time, and we lost that unity for a while after. Ævar was a softer character than the rest of the band. He listened to Sting and liked Laurie Anderson way too much. He wore glasses and we didn’t like that either, even though Óttarr also wore glasses too. In the end we got hot headed and thought we were too much of a rock band for Ævar’s soft drumming. We let him go and he has been thankful to us ever since.”

“We were making the album ‘Buffalo Virgin’ at the time and got Hallur Ingólfsson to drum for us. You can hear in ‘Buffalo Virgin’ that we weren’t a functioning band at the time. Hallur came from a heavy metal background, which we thought was funny, as we had started to make fun of heavy metal. We had started to listen to The Cult and rock music like that, and wanted more ‘rock’ elements in our sound. No one else in our circle, the Bad Taste circle, was thinking about metal or anything of the kind. Hallur played with us for a year, and we developed in a certain direction with him aboard. Songs like ‘Animalia’ were born at the time.”

“However, Hallur had ambitions to write songs and of course I had no interest in that. I have always written the HAM songs. I am not a dictator in the band though. Most of the time, the other members know better than I what is a good HAM song. For every song we make, there are maybe ten that get tossed away. Often I have difficulties when presenting new songs to the band, because I am so afraid of their opinion. They have controlled me just as much as I have controlled them—and maybe that’s the foundation of our quality. We have a very strict quality control.”

The final nail in the HAM coffin

After Hallur quit in 1990, HAM found their third (and current) drummer in Kópavogur. A boy several years younger than the rest of the band, Addi.

“He was the final nail in the, ehrm, HAM coffin. A great, powerful drummer, but with a simple style. He never shows off. Nobody in HAM ever shows off. At this time we were 100% in HAM. In 1991 we started planning a move to New York City, as there was nothing to be done in Iceland. In the spring of 1993, we finally went there and it was a kind of make or break situation for the band. It was a hustle. We played lots of small clubs, CBGB’s twice, and got good feedback but we just couldn’t stay in the city longer than six months, money wise. The Icelandic króna collapsed while we were abroad, so that shortened our stay, too.”

“It was in the wake of this trip that I started wondering why everything worked much easier in the film industry than in the music business. At the time I was working with [fabled Icelandic director] Óskar Jónasson. It appeared to me that rock music was not a foundation that I could live off in the future, but that my chances could lie in films and the comedy business. I had watched a lot of TV in New York, and was influenced by things like Saturday Night Live and David Letterman. I got interested in exploring more fields. In 1994 me and Magga Stína [who was singer in the Bad Taste band Reptile] and Jón Gnarr started our first radio show, ‘Heimsendir’ [“The End Of The World”]. It had been apparent since we met that Jón and I would eventually do something together.”

HAM is dead, long live HAM

HAM played what was supposed to be their last ever concert in June of 1994, with recordings from the show being released in CD form as ‘HAM lengi lifi’ (“Long Live HAM”).

“I still wanted to make music, and to that end I operated my solo outfit Olympia for one year [an Olympia album and EP were released in 1994 og 1995]. Olympia was more pop than HAM, and OK as such. But in the autumn of 1995, I really couldn’t be bothered with music anymore and dived headfirst into working on stage, in radio and television [his then projects included a staged production of Lazytown, the long-lived ‘Tvíhöfði’ radio show (with Reykjavík Mayor Jón Gnarr) and the ‘Fóstbræður’ (“Blood brothers”) comedy sketch show]. Music was far away in the distance for many years.”

A German rock band, Rammstein, slowly got very popular in Iceland, not the least because people thought it sounded a lot like HAM.

“Record store employees made me listen to Rammstein as soon as 1997, and we presented the band to the nation through the Tvíhöfði radio show. So in 2001, when Rammstein came to play Iceland, there was a lot of pressure on HAM to return. We had kept in touch and Óttarr and I have met regularly for lunch all those years. So we thought, why not?”

HAM supported Rammstein in Laugardalshöll for a two show stint, playing for about 10.000 people in total. A sort of HAM legend had developed in Icelandic rock circles—maybe because of Sigurjón’s daily presence on the radio and the enduring popularity of [aforementioned director Óskar Jónasson’s] ‘Sódóma Reykjavík,’ a 1992 comedy wherein HAM play a large part (it was recently voted the most beloved Icelandic film). The band’s return was touted as the birth of the son of Satan, and the HAM legend still lingers on.

HAM are quick like a glacier

“The comeback was fun, and in the aftermath I started relating again to this world. I thought that it would be fun to meet those entertaining men on a somewhat regular basis and engage in something creative together. A plan of sorts was laid out in 2006, when we performed again in public. In the five years since, the songs on the new album started to come forward. I have to be in HAM to be able to write HAM songs. We have to have a goal, like practicing for a concert, and we have to meet regularly for me to be in the mood for writing a HAM song. I couldn’t write a HAM song in the Canary Islands! It’s inbred. From being in HAM, a HAM song sprouts. We have maybe played twice a year for the last few years, and two new songs appear annually. Slowly we had readied a ten track album…”

And now, after twenty-two long years, a brand new HAM album is finally out! It’s called ‘Svik, harmur og dauði’ and it is available for purchase on CD, vinyl and in various digital formats.

“It’s a dark and dramatic album. What has always fascinated us is to make dramatic and wistful music. But earlier we were just a group of twenty-two year old happy dudes, and couldn’t really put it forth convincingly. Over the years I have matured and experienced lots of drama in my life. I think all this has found its way into the music. This kind of album couldn’t have been made in 1989. We just didn’t have the maturity or the experience. This is a dramatic album, and Óttarr’s lyrics mirror all the drama.

The lyrics are not about our personal drama or experiences; they are inspired by the music. It’s always like that. First comes the music, then the lyrics. I’m very content with this album. It took five years to make, but only three days to record. I have no idea if we’ll ever make another album. There are no new songs. But who knows, maybe in 2016, five years from now. At least we have a title for a new album: ‘Heimspekingurinn, fávitinn og hóran’ (“The Philosopher, the idiot and the whore”). There must be a concept!”

Keep doing what you love

By now, many of Sigurjón’s friends are deep in the business of running the city of Reykjavík, thanks to The Best Party’s freak election victory. Does he regret not taking a more active part in The Best Party business with his friends?

“No! For a little while I wondered whether I should be more into it, but fortunately I didn’t do it. When the election struggle was going on, my wife and me were having a daughter and then of course, I live in Kópavogur. I always thought that I was the one in Tvíhöfði with more political interest, but I was obviously very wrong!”

“I don’t think I will ever go into politics. It’s just way more constructive and fun to do what I do. To be creative in many fields. I am a screenwriter and producer for TV shows [currently ‘Pressan’, season three and ‘Ástríður’, season two, both for Stöð 2], and I am developing various exciting things. I’m writing a movie, a horror film called ‘The Girl And The Devil’. I am always doing something that’s fun. I owe it to myself to be creative all day long, as I think I have the gift for it. You can definitely be a creative politician, like Jón obviously is, but the environment is very difficult, so the job takes up a lot of energy. You’re being bothered all day long. It’s a dilemma you face, and my choice was to keep on doing what I love.”

—

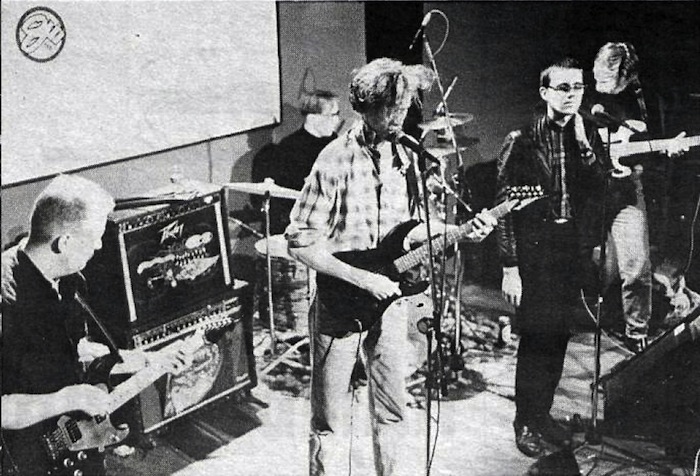

Classic HAM in 1993.

1987: Sigurjón sees Swans in London. Forms HAM with Óttarr Proppé (vocals), Björn Blöndal (bass) and Ævar Ísberg (drums). The first HAM rehearsal takes place just before New Year’s Eve.

1988: The first HAM gig, in March. The five track ‘HOLD’ 12″ EP is releasedby Smekkleysa/Bad Taste in July. A video for ‘Trúboðasleikjarinn’ (“The Missionary Licker”) is banned on national TV. It features Stefán Karl, punk band Fræbbblarnir’s drummer, swinging naked on a cross smeared in blood. Dr. Gunni joins on second guitar. In October, Pere Ubu’s David Thomas refuses to let HAM support the band when they perform in Reykjavík, after witnessing their soundcheck. Jón Egill Eyþórsson joins HAM after Dr. Gunni leaves.

1989: Drummer Ævar is fired for being ‘too soft.’ In protest, Jón Egill quits. Drummer Hallur Ingólfsson and guitarist Flosi Þorgeirsson join the band. HAM play the New Music Seminal in New York as part of Bad Taste’s ‘World Domination Or Death’ masterplan. Bless, Reptile and poet Jón Gnarr appear as well. The ‘BUFFALO VIRGIN’ LP is released by One Little Indian in the UK. HAM supports The Sugarcubes on a UK tour. A drunk Flosi severely insults NME’s left-wing scribe, Seething Weels, with one too many politically incorrect phrases. HAM’s reputation with the UK music press is consequently deemed beyond repair.

1990: Arnar Geir Ómarsson, Addi, replaces drummer Hallur. HAM record a new album, ‘PIMPMOBILE’. It is never released—the official reason is that it got lost when the US branch of Rough Trade Records went bankrupt. HAM hustle and play the Icelandic rock locals, often with bands like Sororicide from the then-burgeoning death metal scene.

1991 – 1992: Jóhann Jóhannsson [Apparat Organ Quartet, solo] joins on guitar and keyboards. He has already been with Sigurjón and Óttarr in the funk band Funkstrasse. Sigurjón plays the role of rock musician Orri in Óskar Jónasson’s comedy ‘Sódóma Reykjavík’. He writes music for the film—including a guitar riff that will later ends up as the basis of Quarashi’s hit song ‘Stick ‘Em Up’. HAM record new songs for the film with ex-Swans member Roli Mosiman. This includes HAM’s most famous song, ‘Partýbær.’ Björk Guðmundsdóttir, Óskar’s girlfriend at the time, plays organ in the song. Sódóma Reykjavík is premiered in October 1992. Legendary status ensues. HAM appear in the film as Helía. A documentary entitled ‘HAM Í REYKJAVÍK’ is released on VHS in a limited edition of 100 copies.

1993: Flosi quits. ‘SAGA ROKKSINS 1988-1993’ (“A History Of Rock 1988-1993”) is released by Bad Taste in May. It is a compilation featuring songs from the ‘Pimpmobile’ and Sódóma sessions and the whole of the ‘HOLD’ EP. In June, HAM start their New York City tenure and play several shows, including some at CBGB’s. A live recording of the CBGB gig is released on CD in 2001 as ‘CBGB‘s 7. ÁGÚST 1993.’ In New York, they meet Páll Óskar and Sigurjón and Jóhann wind up helping make Páll’s first album, ‘Stuð’ when they return to Iceland that autumn.

1994: HAM decide to call it quits. In June they play their “last concert ever” at Tunglið. A live album, ‘HAM LENGI LIFI’ (“Long Live

HAM”) is subsequently released.

1995: Skífan releases ‘DAUÐUR HESTUR’ (“Dead Horse”), a collection of songs from the Sódóma period.

2001: HAM come back to perform at two Rammstein concerts in Reykjavík. They also play on their own at the club Gaukur á Stöng.

Recordings from that gig are released as ‘SKERT FLOG’ (“Curtailed Seizure”). A second HAM documentary, ‘HAM—Lifandi dauðir’ (“HAM—Living Dead”), premieres in December.

2006 – 2010: HAM return once more in 2006, (with Flosi but sans Jóhann) and now with a new song, ‘Sviksemi’ (“Deceit”) that they premier on TV. The band is “back for good”, performing once or twice a year, more often than not at the Eistnaflug metal festival in Neskaupsstaður, or at Iceland Airwaves. New songs are added annually.

2011: A new studio album, with ten new songs is released!

HAM play Tunglið to promote ‘SAGA ROKKSINS 1988-1993’ in 1993.

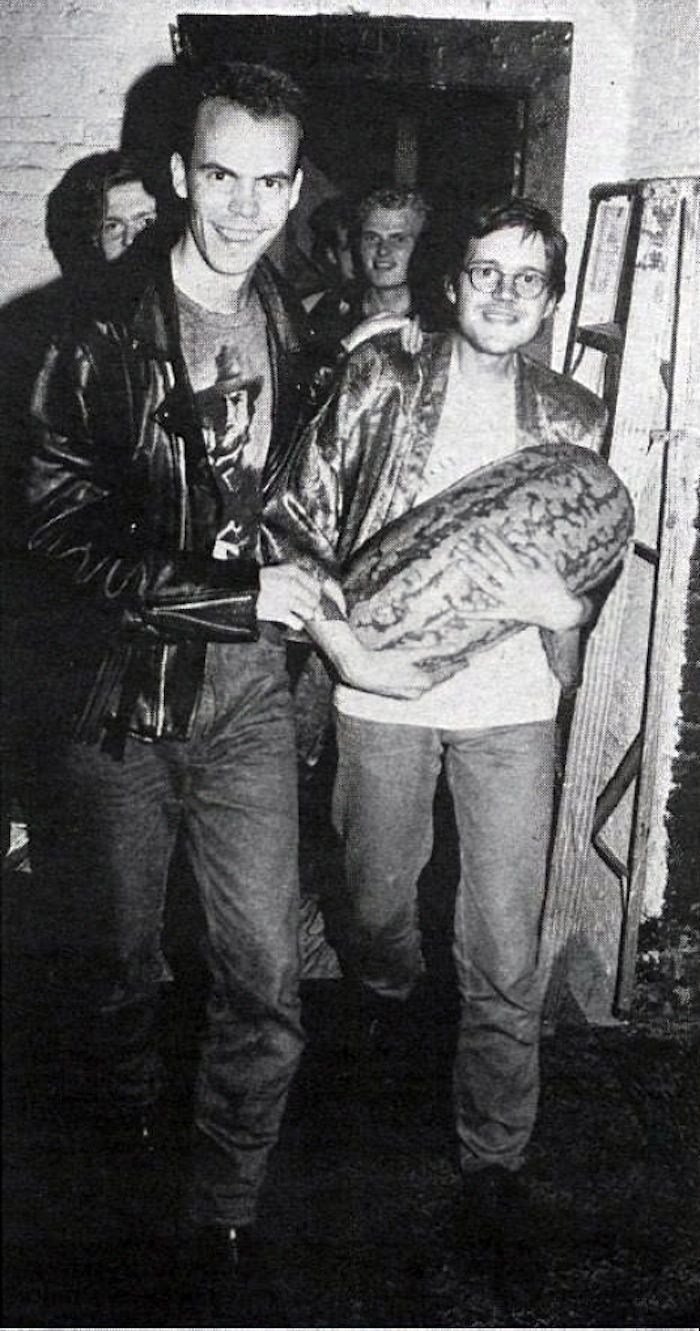

Sigurjón, Jóhann and Páll Óskar make Páll’s debut album, Stuð.

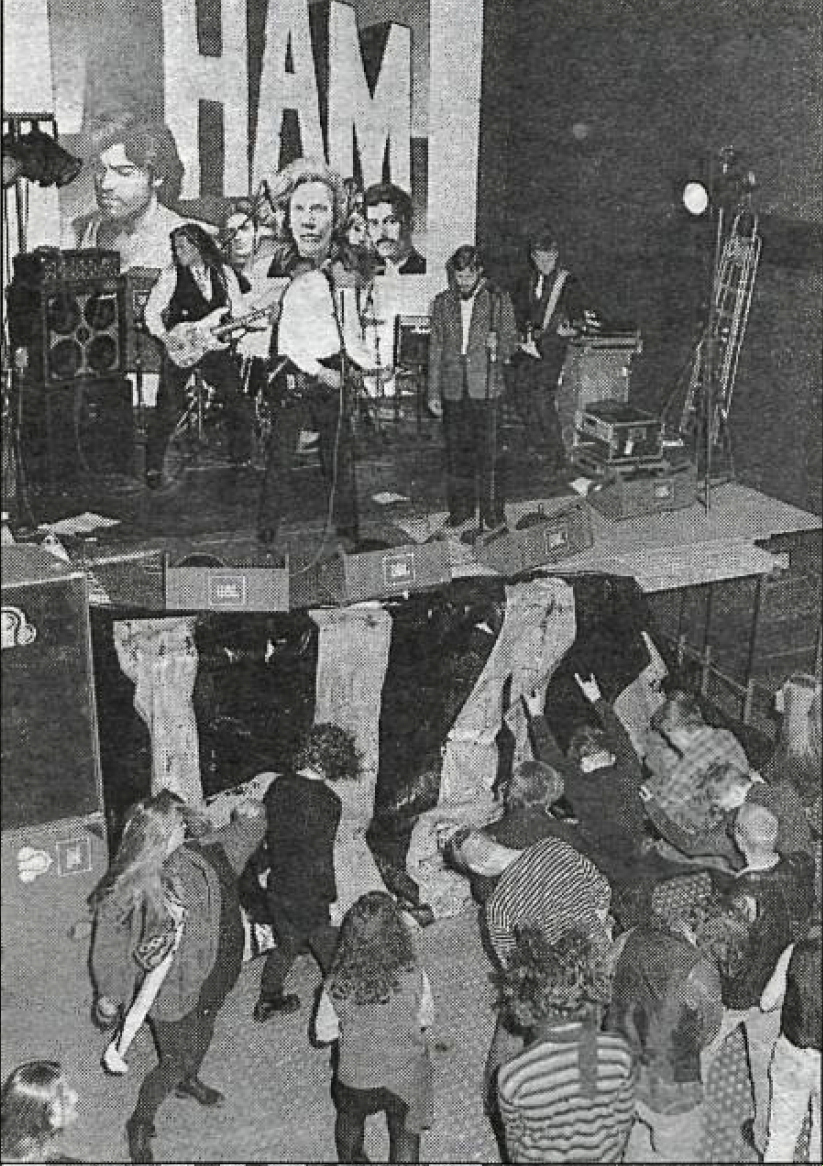

HAM today.

WHY DO ICELANDERS

LIKE HAM?

People like HAM because of their lightly absurd mix of coolness and humour. The group behind HAM is far reaching within the creative sector. It gathers a certain group, a kind of ‘rock elite’ for Iceland, which many people wish to partake in. Then, some people might like HAM because someone told them to.

Anna Margrét Björnsson,

HARPA PR Representative

While most people make a clear distinction between what is supposed to be funny and what serious, Icelanders have never seen much reason to do so. So when HAM play their mixture of brutal rock ‘n’ roll riffs and witty lyrics that would get lost in any translation, Icelanders simply get it.

Páll Ragnar Pálsson,

musician, composer

HAM is also a cheese. Cheese is best when it’s gotten a little old and mouldy. Nothing is worse than unripe cheese—at the same time, nothings better than Gamle Ole mixed with fresh whitebread, butter and jam. Every Icelander knows this.Last but not least, HAM is like mature sex. Youth’s awkwardness and inexperience are left behind and replaced by trust. Anyone that’s tried can attest: sex gets better as you grow older. HAM are at the peak of their maturity and experience, and the Icelandic nation is the fortunate lover.

Grímur Atlason,

Iceland Airwaves Festival Director

Because HAM is simply the best rock band ever! They are good for every occasion; for drinking, for partying, for driving fast. Their music is upbeat, but still depressing, just like our nation.

Guðmundur Óli Pálmason,

drummer, SÓLSTAFIR

Icelanders connect with HAM because of their music’s heaviness and pathos. Sigurjón’s father was a church organist, and I think that greatly influenced ‘The Duke’, as he is called. The dramatic sorrow—and the epic nature—of the songwriting resonates with the extreme opposites presented by our seasons. We like HAM for the same reasons that Finnish people like vodka and saunas. Icelanders seem to have a knack for spotting pretentiousness. And even though HAM certainly possess a certain constructed drama, the music’s power and ferocity is sincere and real. That’s how it is.

Birgir Örn Steinarsson,

writer, musician, DJ

I suppose they think HAM are cool. The comedy ‘Sódóma Reykjavík’ plays a large part, I suppose. Movies have a way of building cults. I was at a lot of HAM shows back in the day, and people weren’t exactly queuing up to attend. They’ve done things right since. They’ve aged very gracefully, their comeback was very tasteful and they’ve managed to build on their ‘cult reputation’ very nicely.

Ólafur Páll Gunnarsson,

Head of Music, Icelandic State Radio (Rás 2)

Do Icelanders even like HAM? I remember when no one in Iceland liked HAM except for me and my friends. Now everyone loves them. I suppose it’s a mix of many things. Their music sounds like metal at first listen, but lacks a lot of what makes metal ‘metal’. It’s a basic rock, with a drone, no power breaks. I think it’s mainly HAM’s persistent nature that has won them their place in Icelanders’ hearts. They’ve been going at it for twenty-something years by now, and have managed to appeal to at least two generations in the process.

There are also other things. The bandmembers are all characters, and some of them are beloved comedians or public persons. But mainly, HAM are just awesome. And persistent.

Árni Sveinsson,

filmmaker

HAM consists of men that have sort of been deputised by nature itself. They are born leaders, and now, when they’ve been doing this for what, thirty years? Twenty-five years? In any case, they have reached the stage and age where they don’t need to try anymore. They are just naturally cool. They’ve always possessed it, this incredible, Old Icelandic SHERIFF POWER. You look at these men, you don’t hesitate, you just know. They are self-appointed chieftains, you don’t fuck with that.

Mugison, musician

WHY DO ICELANDERS

LIKE HAM?

Picture this: An Icelandic television talk show in the early ‘90s. A young man is describing his life in Denmark, where he had been studying. Asked about how closely he had followed news from Iceland during his studies he says: “Well, somehow I thought that HAM was the most popular band in Iceland, since they were always being mentioned in Morgunblaðið. When I came home, however, I found this not to be true, no one knew what I was talking about.”

Today is widely accepted in Iceland that HAM is the best band ever to appear in Iceland, never mind Sigur Rós or the Sugarcubes. In fact, people are known to proclaim loudly (when inebriated) that HAM actually is the best band to emerge in the World. Ever. This is relatively new, as you can infer from the quotation above. In fact, when HAM were active, in the late ‘80s (the first gig was in Lækjartungl in downtown Reykjavík, March 10, 1988—the following day Lækjartungl was closed for good) people generally didn’t know what to think of the band. One reviewer for Morgunblaðið called HAM the most boring band of our times—already HAM was generating superlatives, but for all the wrong reasons.

The idea that HAM was well known and generally liked from the start is thus obviously not true. Yes, there was a vocal core of people that loved the band from the start, but it took several years for people in general to understand what HAM was all about. The crowd that loved The Sugarcubes, Reptile and S/H Draumur mostly found HAM to be too loud, too aggressive and too ugly. One memorable incident was in October 1988, when Pere Ubu, those paladins of propriety, came to Iceland and HAM was supposed to support them in Tunglið (ex. Lækjartungl). When David Thomas heard HAM play at the sound check he refused the support. Even metalheads, who tend to like angry, ugly and loud music, didn’t like HAM, they were too sloppy and had terrible dress sense.

Soon after HAM folded in the autumn of 1993 a new generation of musicians and music fans started to appreciate the band and HAM became legendary. Their support of Rammstein was an eye opener for most of the rock fans in the Laugardalshöll-stadium, and later they were invited to play at Iceland’s premier hard rock festival, Eistnaflug, in 2008. So what is it people like about HAM? The short answer is: HAM is the quintessential Icelandic band, the distillation of Icelandic humour, black as sin. HAM is just like us when we are drunkhappyloud and also just like us when we are drunkangrysad and everything in between. You don’t have to be Icelandic to enjoy HAM, but it helps. A lot.

Árni Matthíasson, journalist

Buy subscriptions, t-shirts and more from our shop right here!